Duality exercises

Exercise 1 is easy: at the end of Chapter 2 the corresponding products statement was proved, and the obvious dual statement turns out to be this one.

Exercise 2 falls out of the appropriate diagram, whose upper triangle is irrelevant.

Exercise 3 I’ve already proved - search on “sleep”.

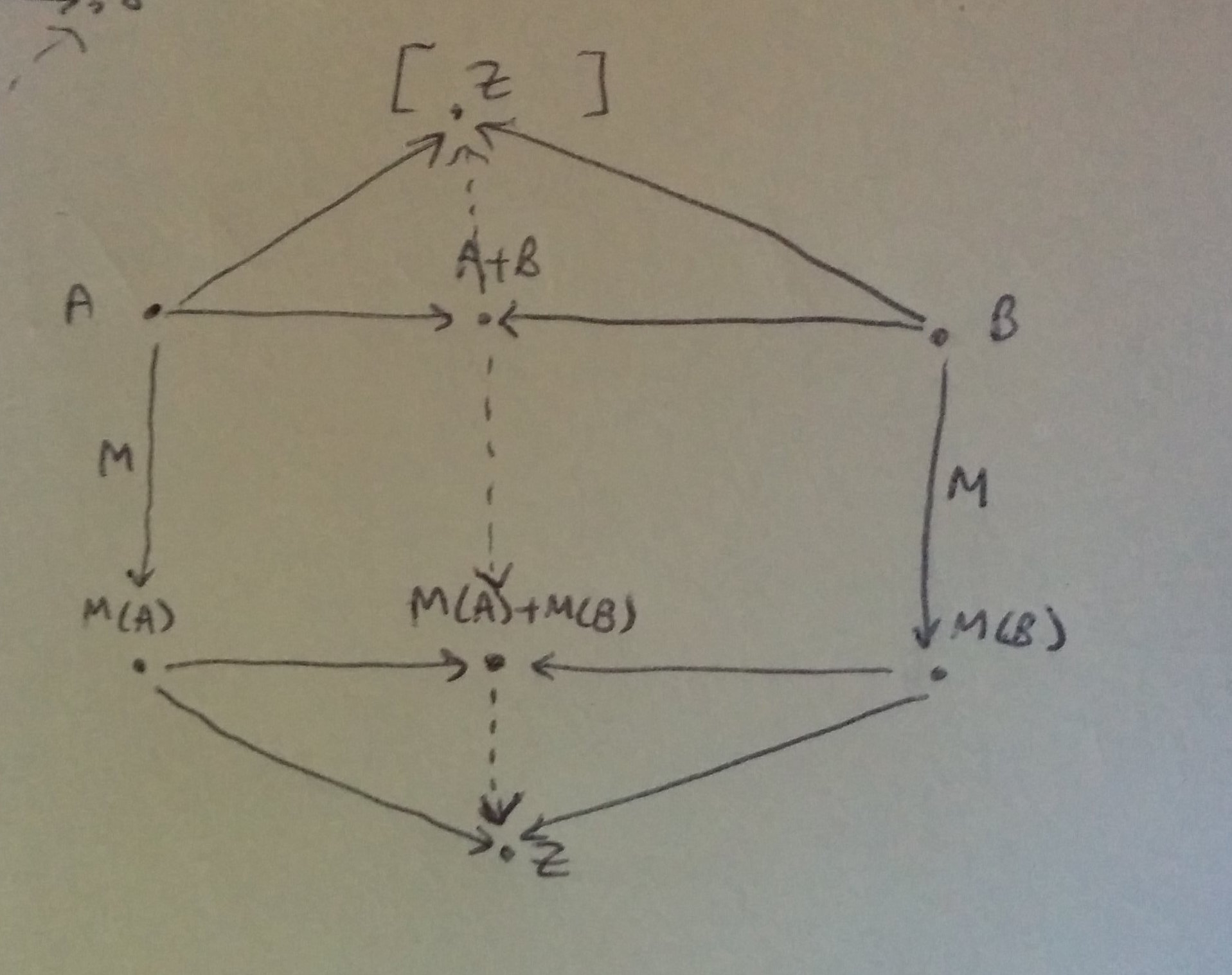

Exercise 4: Let \(\pi_1: \mathbb{P}(A + B) \to \mathbb{P}(A)\) be given by \(\pi_1(S) = S \cap A\), and \(\pi_2: \mathbb{P}(A+B) \to \mathbb{P}(B)\) likewise by \(S \mapsto S \cap B\). Claim: this has the UMP of the product of \(\mathbb{P}(A)\) and \(\mathbb{P}(B)\). Indeed, if \(z_1: Z \to \mathbb{P}(A)\) and \(z_2: Z \to \mathbb{P}(B)\) are given, then \(z: Z \to \mathbb{P}(A + B)\) is specified uniquely by \(S \mapsto z_1(S) \cup z_2(S)\) (taking the disjoint union).

Exercise 5: Let the coproduct of \(A, B\) be their disjunction. Then the “coproduct” property is saying “if we can prove \(Z\) from \(A\) and from \(B\), then we can prove it from \(A \vee B\)”, which is clearly true. The uniqueness of proofs is sort of obvious, but I don’t see how to prove it - I’m not at all used to the syntax of natural deduction. I look at the answer, which makes everything clear, although I still don’t know if I could reproduce it. I understand its spirit, but not the mechanics of how to work in the category of proofs.

Exercise 6: we need that for any two monoid homomorphisms \(f, g: A \to B\) there is a monoid \(E\) and a monoid homomorphism \(e: E \to A\) universal with \(f e = g e\). Certainly there is a monoid hom \(e: E \to A\) with that property (namely the trivial hom), so we just need to find one that is “big enough”. Let \(E\) be the subset of \(A\) on which \(f = g\), which is nonempty because they must be equal on \(1_A\). I claim that it is a monoid with \(A\)’s operation. Indeed, if \(f(a) = g(a)\) and \(f(b) = g(b)\) then \(f(ab) = f(a) f(b) = g(a) g(b) = g(ab)\). This also works with abelian groups - and apparently groups as well.

Finally we need that this structure satisfies the universal property. Let \(Z\) be a monoid with hom \(h: Z \to A\), such that \(f h = g h\). We want a hom \(\bar{h} : Z \to E\) with \(e \bar{h} = h\). But if \(f h = g h\) then we must have the image of \(h\) being in \(E\), so we can just take \(\bar{h}\) to be the inclusion. This reasoning works for abelian groups too. We relied on Mon having a terminal element and monoids being well-pointed.

Finite products: we just need to check binary products and the existence of an initial object. Initial objects are easy: the trivial monoid/group is initial. Binary products: the componentwise direct product satisfies the UMP for the product, since if \(z_1: Z \to A, z_2: Z \to B\) then take \(z: Z \to A \times B\) by \(z(y) = \langle z_1(y), z_2(y) \rangle\). This is obviously homomorphic, while the projections make sure it is unique.

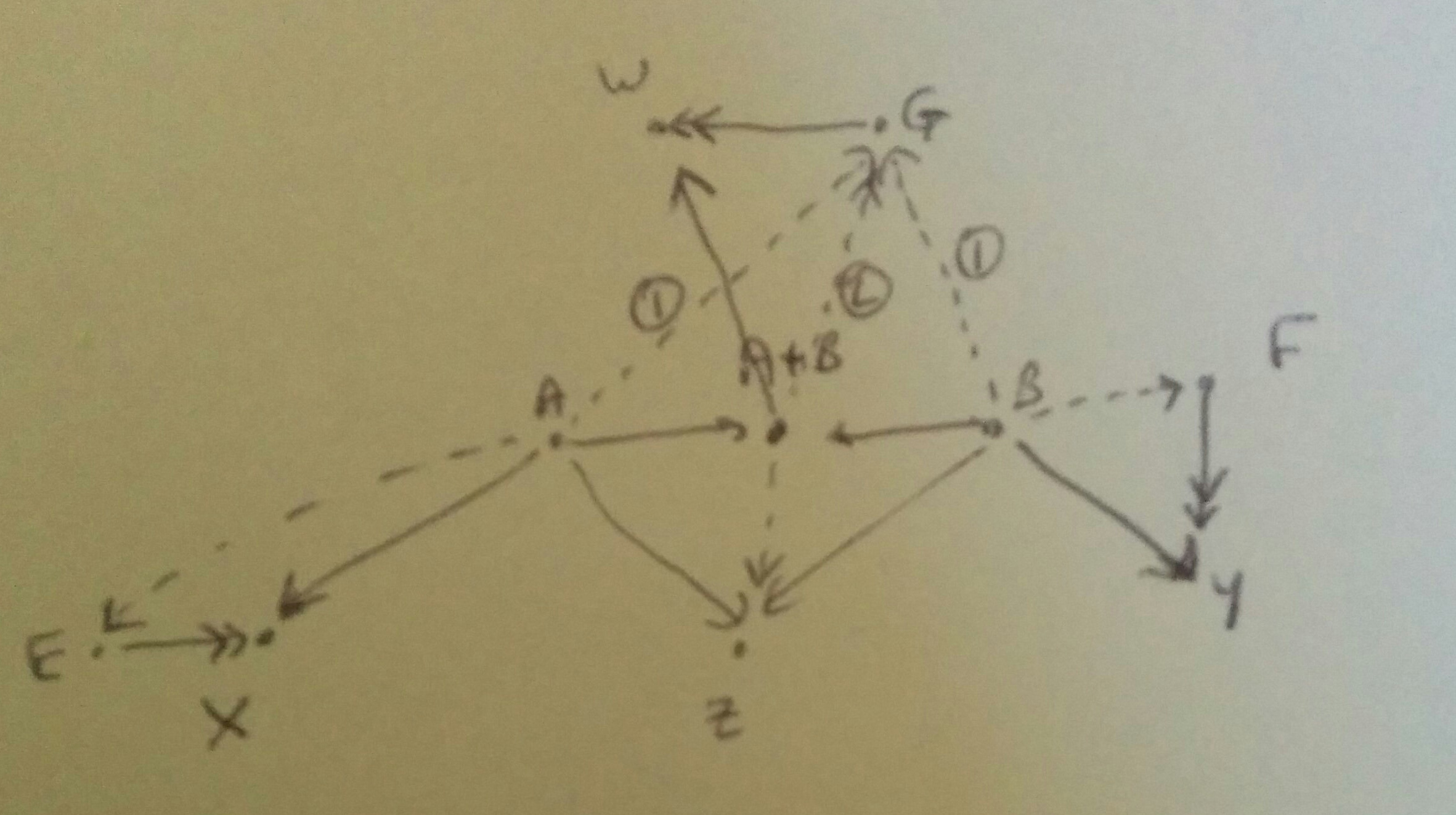

Exercise 7 falls out of another diagram. The (1) label refers to arrows forced by the first step of the argument; the (2) label to the arrow forced by the (1) arrows.

Exercise 8: an injective object is \(I\) such that for any \(X, E\) with arrows \(h: X \to I, m: X \to E\) with \(m\) monic, there is \(\bar{h}: E \to I\) with \(\bar{h} m = h\). Let \(P, Q\) be posets, and let \(f: P \to Q\) be monic. Then for any points \(x, y: { 1 } \to P\) we have \(fx = fy \Rightarrow x=y\), so \(f\) is injective. Conversely, if \(f\) is not monic then we can find \(a: A \to P, b: B \to P\) with \(fa = fb\) but \(a \not = b\). This means \(A = B\) because the arrows \(fa, fb\) agree on their domain; so we have \(a, b: A \to P\) and \(x \in A\) with \(a(x) \not = b(x)\). But \(f a(x) = f b(x)\), so we have \(f\) not injective.

Now, a non-injective poset: we want to set up a situation where we force some extra structure on \(X\). If \(I\) is has two distinct nontrivial chunks which have no elements comparable between the chunks, then \(I\) is not injective. Indeed, let \(X = I\). Then the inclusion \(X \to I\) does not lift across the map which sends one chunk “on top of” the other: say one chunk is \({a \leq b }\) and the other \({c \leq d}\), then the map would have image \(a \leq b \leq c \leq d\).

What about an injective poset? The dual of “posets” is “posets”, so we can just take the dual of any projective poset - for instance, any discrete poset. Anything well-ordered will also do, suggests my intuition, but I looked it up and apparently the injective posets are exactly the complete lattices. Therefore a wellordering will almost never do. I couldn’t see why \(\omega\) failed to be injective, so I asked a question on Stack Exchange; midway through, I realised why.

Exercise 9: \(\bar{h}\) is obviously a homomorphism. Indeed, \(\bar{h}(a) \bar{h}(b) = h i(a) h i(b) = h(i(a) i(b))\) because \(h\) is a homomorphism. But \(i(a)\) is the wordification of the letter \(a\), and \(i(b)\) likewise of \(b\), so we have \(i(a) i(b)\) is the word \((a, b)\), which is itself the inclusion of the product \(ab\).

Exercise 10: Functors preserve the structure of diagrams, so we just need to show that that the unique arrow guaranteed by the coequaliser UMP corresponds to a unique arrow in Sets. We need to show that given a function \(\vert M \vert \to \vert N \vert\) there is only one possible homomorphism \(M \to N\) which forgetful-functors down to it. But a homomorphism \(M \to N\) does specify where every single set element in \(\vert M \vert\) goes, so uniqueness is indeed preserved.

Exercise 11: Let \(R\) be the smallest equiv rel on \(B\) with \(f(x) \sim g(x)\) for all \(x \in A\). Claim: the projection \(\pi: B \to B/R\) is a coequaliser of \(f, g: A \to B\). Indeed, let \(C\) be another set, with a function \(c: B \to C\). Then there is a unique function \(q: B/R \to C\) with \(q \pi = c\): namely, \(q([b]) = c(b)\). This is well-defined because if \(b \sim b’\) then \(c(b’) = q([b’]) = q([b]) = c(b)\).

Exercise 12 I’ve already done - search on “wrestling”, though I didn’t write this up.

Exercise 13: I left this question to the end and couldn’t be bothered to decipher the notation.

Exercise 14: The equaliser of \(f p_1\) and \(f p_2\) is universal \(e: E \to A \times A\) such that \(f p_1 e = f p_2 e\). Let \(E = { (a, b) \in A \times A : f(a) = f(b) }\) and \(e\) the inclusion. It is an equivalence relation manifestly: if \(f(a) = f(b)\) and \(f(b) = f(c)\) then \(f(a) = f(c)\), and so on.

The kernel of \(\pi: A \mapsto A/R\), the quotient by an equiv rel \(R\), is \({ (a, b) \in A \times A : \pi(a) = \pi(b) }\). This is obviously \(R\), since \(a \sim b\) iff \(\pi(a) = \pi(b)\). That’s what it means to take the quotient.

The coequaliser of the two projections \(R \to A\) is the quotient of \(A\) by the equiv rel generated by the pairs \(\langle \pi_1(x), \pi_2(x) \rangle\), as in exercise 11. This is precisely the specified quotient.

The final part of the exercise is a simple summary of the preceding parts.

Exercise 15 is more of a “check you follow this construction” than an actual exercise. I do follow it.